By Amy Lutz, MCWC Operations Manager

Yes, you heard that right: MCWC will be venturing ONLINE for this year’s conference. In light of COVID-19 and Califonia’s shelter-in-place measures, we cannot safely welcome participants to the Mendocino Coast for MCWC 2020. But we feel that writing and community are as important now than ever, and have decided to offer a virtual experience in line with the instructive, supportive, and celebratory conferences we’ve provided for the last thirty years.

This year, though we cannot be together in person, we have the chance to create a conference that will connect us in this time of isolation and loneliness. We are embracing the opportunity to redesign our gathering and bring our cherished traditions—deep and productive workshops in ten subjects, afternoon seminars presented by a range of faculty, opportunities to consult with publishing industry experts, readings by our world-class authors, open mics, and other opportunities to make connections—to our participants from across the distance.

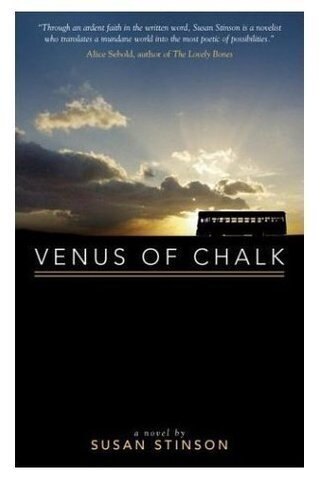

In this month’s spotlight interview, we are featuring MCWC’s first-ever historical fiction workshop instructor, Susan Stinson. Winner of the Lambda Literary Outstanding Mid-Career Novelist Prize, Susan is the author of four novels, including Martha Moody (soon to be reissued by Small Beer Press), Venus of Chalk (Lambda Literary Finalist), and Fat Girl Dances with Rocks. Her latest novel, Spider in a Tree (Small Beer Press), is inspired by Northampton, Massachusetts in the time of eighteenth century preacher and slave-owner Jonathan Edwards.

Though your latest novel may appear to be a departure from your previous themes of queerness and body image, you explain the process that led you to write Spider in a Tree in this interview on Bookslut, saying, “I feel that the book, as an object, brings together these different worlds that have always existed in me.” Can you speak a little more about the process of exploration and how you followed your writing into new territory?

One of the things that brought me to write Spider in a Tree is the landscape of Northampton, Massachusetts, where I live. That I am a lesbian and that I wanted to be a writer is why I am here, since I moved here for a relationship more than thirty years ago. This area has a rich history of literary, queer, and adventurous women’s culture, including Emily Dickinson, Smith College, and, as I discovered, Jonathan Edwards. Edwards is an important part of literary—he’s an extraordinary writer—and religious history, and at first it felt transgressive for me to write about him since all of my previous books had centered on the complex lives of fat lesbians. But much of his family is buried in the cemetery across the street from my apartment. I ran across the gravestones as I walked and wrote there, and began imagining their lives. I was raised a Protestant, and am a descendant of English immigrants from many generations back, so this felt like a story that was part of my heritage. Calvinist attitudes towards the body and sexuality had profoundly shaped me (and many contemporary institutions) without me being fully aware of it. When I learned that people were enslaved in the Edwards household, an exploration of what that meant, and continues to mean, became central to the story.

In this interview with Write Angles, you describe the ten-year writing and researching process behind Spider in a Tree. Did you anticipate the book would be such an intensive project? Did the research come naturally to you or was it a skill set you had to develop? How did you keep momentum for the project over such a long writing period?

I had no idea how long it would take when I started! I had to learn the skills for research. They were much more varied and exciting than I expected. I became a bit obsessed. My research took me places like Budapest for a Jonathan Edwards conference, and all sorts of expeditions to find an eighteenth century meeting house, for instance, or details of Jonathan Edwards’s clothing and other household items in his will. The generosity of researchers and scholars was a great gift. The landscape in the town where I live became a kind of living archive. I rode an adult tricycle all over town, and wrote outside in all seasons, trying to get direct sensory information for my explorations in the past. The urgency of all I didn’t know kept me going. I started giving cemetery tours once a year around Jonathan Edwards’s birthday, and the ongoing interest the people who showed up for those and for readings gave me a boost, too.

When I read Spider in a Tree, I was impressed by your ability to capture the culture of the characters in such a complete way; I felt like I was immersed in a different time period, but could still see the cultural connections between the historical characters and current mindsets present in our society today relating to evangelicalism, sexism, and racism. How much of that successful world building would you attribute to research and how much comes from your imagination?

Thank you. It helped that Jonathan Edwards was a writer, so reading him gave me a direct line into his worldview and the richest eighteenth century Calvinist language—both in his sermons and treatises, and also in his letters and other personal writings. He wrote beautifully about his wife, Sarah, when he was courting her. One big challenge for this book was that there was so much writing and scholarship that centered on Jonathan Edwards, so how was I going to create deep, accurate characters who saw the world differently? I did as much research as I could, then, grounded in that, I made imaginative leaps. Unexpected imagery came up through insects. I was constantly running into them on my trike rides around town, and Jonathan Edwards included spider and insect imagery in his work, so the rule became that whenever I encountered an insect, I had to stop what else I was doing and write about what it was doing. That helped me find centers of experience other than Jonathan Edwards.

In this interview with Plum, you discuss the choice to follow your passions in writing, rather than pursuing more commercial goals. What advice do you have for writers tackling unique projects that speak to them, but may not be easy to market?

The most important thing in sustaining a life as a writer is to find a community of other writers. Writing friends are invaluable as first readers, cheering squads, and for deepening the pleasure in the process of writing, which—believe it or not—really is the best part. As the current upheavals in life as we know it make very clear, marketing is unpredictable. Writing a good story or a book about something that fascinates you is a transformative experience beyond anything that can be bought or sold.

Would you like to share any thoughts on writing during the current events of COVID-19?

I want to say one thing about writing historical fiction in the time of COVID-19. Writing is inherently an optimistic act because it presumes a future reader. It is an act of trust in the future. For me, stories from the past hold invaluable insights and possibilities. People have been through a lot on this earth. Beings of all kinds, beyond the human, have adapted and survived under tremendous pressure. The life force of all of that survival—along with all of the specific messiness of individual human minds, feelings and relationships—that’s the stuff of wonderful, necessary, urgent, illuminating, comforting art. Writing from history is a way of knowing more about the ground we are standing on. That is such a good way to get ready to take the next step.

To find out more about Susan Stinson, check out her website at www.susanstinson.net.

To register for MCWC 2020 visit mcwc.org. For questions regarding the online conference, email info@mcwc.org.