By Amy Lutz, MCWC Operations Manager

We are thrilled to kick off our MCWC 2020 faculty interview series with a Mendocino County local! This year’s poetry instructor, Michelle Peñaloza, will make the trek over the mountain from Covelo in inland Mendocino County to join us on the coast in August.

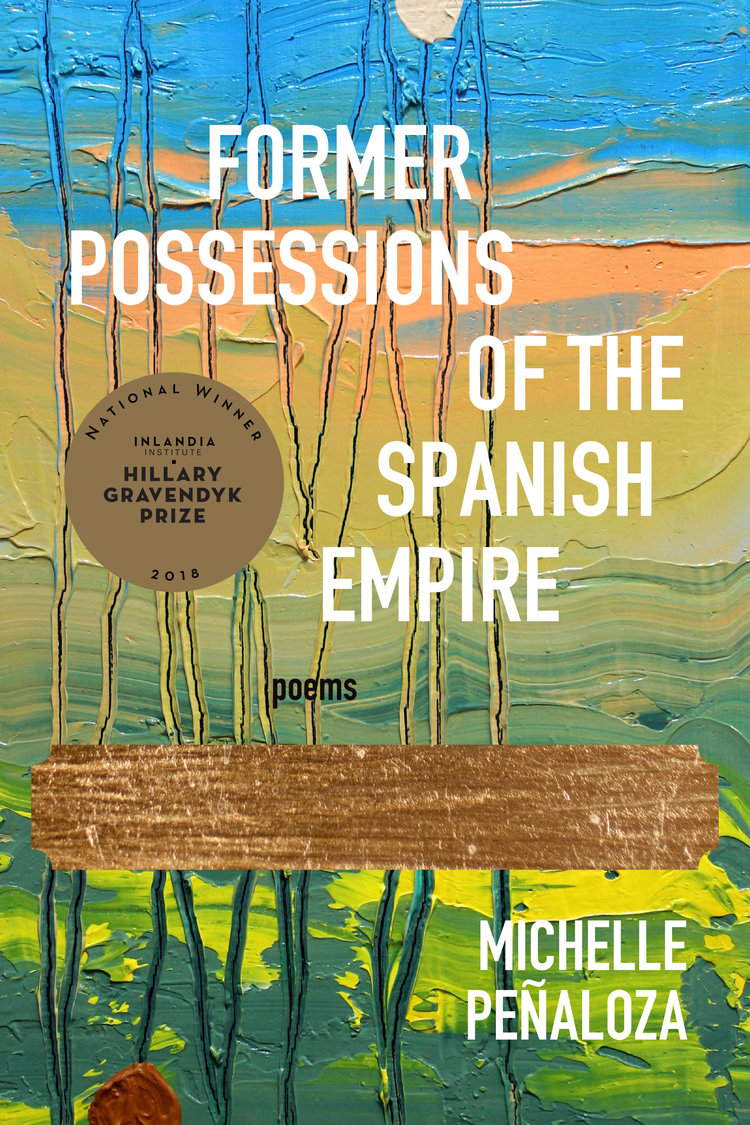

Michelle Peñaloza’s debut full-length collection Former Possessions of the Spanish Empire won the 2018 Hillary Gravendyk National Poetry Prize and was published by Inlandia Books this past August. She’s written two chapbooks, landscape/heartbreak and Last Night I Dreamt of Volcanoes, and her work can be found in River Styx, Prairie Schooner, upstreet, Pleiades, Poetry Northwest and elsewhere. She is the recipient of fellowships from the University of Oregon, Kundiman, and Hugo House as well as the 2019 Scotti Merrill Emerging Writer Award for Poetry from The Key West Literary Seminar.

Michelle shared with us tips for writing about trauma, why she loves poetry, and what she plans to bring to the MCWC 2020 poetry workshop.

Congratulations on the recent release of your new book of poetry, Former Possessions of the Spanish Empire. How are you feeling now that this collection is out in the world? What stands out to you about the publishing process as you look back on the journey?

Thank you so much. I feel great! I’m really proud of the book and honored and heartened by how it’s been received. I’ve been welcomed into so many spaces to share it with so many folks I know and love and also with so many folks I’ve admired from afar that I’ve only met via their poetry and online presence. I suppose what stands out to me is how there is still so much (good, exciting and hard) work involved after the book gets accepted for publication—in terms of shaping its final form, cover design, and then promotion and getting the book into people’s hands. The overwhelming thing, too, is how genuinely excited people are for you and your first book. I think at first I felt a bit sheepish or awkward doing promotion for it, but I was encouraged by dear friends who reminded me how hard I’d worked to write this and how I owed it to my book and myself to put in the time and effort to promote it. They said (and they are right): “It’s a big deal to have a book!”

In this interview with Poetry Northwest, you discuss the role of grief and trauma in Former Possessions of the Spanish Empire, and how writing helped you process those emotions. What was your writing process like in light of that concurrent emotional work? What advice do you have for writers delving into grief and/or trauma in their writing?

The poems in the book were written over the course of ten years so there are varied answers regarding that emotional process in regard to specific poems; however, overall, I’d say that a current that ran/runs through my writing process and the emotional work is that I tried my best to write toward the scariest, hardest things. That thing that Frost says about “no surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader,” I think is applicable to emotion in poems; if I wasn’t feeling the poems in my body, I knew I needed to push myself toward the harder thing.

My advice would be two-pronged: first, get all of your truth on the page—shameful, ugly, raw as it can be. That page is just for you. Then, always apply and return to your craft. We all suffer, we all experience trauma. The facts and processing of experiences don’t make poems in and of themselves. Turn to craft. Turn to the poets that have opened you up with their work, that have helped you understand something more about your own truth. Ask, study: how did they do that? How did the craft of their work do that to you, for you? Then, be exacting, be ruthless in your evaluation of what in your own writing craft serves the truth you hope to communicate. Grief and trauma are not new, nor is writing about them; however, your writing can only ever be yours and that is where your power comes from.

The poems in your chapbook landscape/heartbreak evolved out of a project you undertook in Seattle, in which you met with people in various places where they had been heartbroken and listened to their stories while walking. You detail the development of the project in this interview with International Examiner. Can you share a little more about how/why you embarked on a project involving stories from other people? How was the process of reaching out, gathering material, and turning it into poetry?

Thanks for this question. Though it’s been several years, this project is still very dear to me. As to how I embarked: I simply asked people to share their stories (first people I knew) and then it took off from there—via word of mouth, via more folks learning about what I was doing. People began to find me. People really wanted to be a part of the project. People wanted to share their heartbreaks and the places in which they took place. As to why I embarked on the project involving other people's stories...it felt lonely and small to be centered on my own heartbreak alone. As I said in the aforementioned interview, I thought about how the act of walking had given me the strength to leave and process my own hard, traumatic situation and how my experience of walking conversations had been clarifying and heartening. I thought, what if I asked other people to walk with me? What if I, being so new to Seattle, learned the landscape of the city through people’s stories? What if my heart could heal in tandem with others?

The process was actually a very organic one; as only folks who were into the project and open to share their stories and go on the walks where the ones who participated, people were already pretty open by the time we went on our walks. I recorded all of the conversations and then listened to them after the walks and then worked from there. My intimate knowledge of all the participants’ generously shared stories were an intrinsic part of each poem for me. So, that said, a great anxiety of mine throughout the making of the poems was the task of doing justice and paying homage to the openness and vulnerability of the people who took me on walks. Not every walk inspired a entire poem. Not every attempt to write a poem was successful enough to do justice to a story someone had shared with me. Still, I wanted to acknowledge every walk as a part of the project, which I did in the chapbook’s final poem, which I aimed to also correspond with the final map in its form. I think of these smaller pieces as “inside poems” shared between me and the people with whom I walked. These small moments may read as more esoteric than the rest of the collection, but I hope they resonate for every reader, and, I believe, taken as a whole will reiterate the culmination of story and transformation of place in landscape/heartbreak.

You now live on a farm in rural Mendocino County. So many of us here at MCWC have stories of the magic that seemed to draw us to this special place. What brought you to Mendocino and what do you enjoy about living here?

Love brought me here! I left Seattle to be with my then-boyfriend, now-husband. I loved living in Seattle, but it was hard to be apart from my person and also hard to keep experiencing the reality of how hard it is to plant sustainable roots in a city that is so expensive and (continues) rapidly growing more expensive. So, it was a multi-faceted decision.

I enjoy so many things about Mendocino County. I love the seasons; I love the red bud that blooms in the mountains; I love swimming in the rivers; I love being able to buy a permit, snowshoe a bit, and then cut down my own Christmas tree. Mendocino County is gorgeous. And it is very raw and rare in it’s beauty. Covelo, specifically, is unlike anywhere I have ever lived and the community I’ve found here is much like the landscape: beautiful, raw, and rare, too. Living rurally has taught me so many new things about how community shows up and manifests.

Can you share with us about your teaching style and what you love about the craft of poetry? What do you hope to bring to the poetry workshop at MCWC 2020?

I like to think I’m pretty fun. I am a passionate teacher; I use my hands a lot, I’m a bit loud and I am very excited to talk about poetry. What do I love about the craft of poetry? Poetry incites the very practical expansion of one’s capacity for empathy and connection to the world outside the self. Poetry teaches us to read the complex simultaneity of the world—the many truths contained in single moments, the music beneath our transactions of language, the lived intersections of our experiences and identities. I also love the specificity of the craft of poetry—the many forms and genres and devices and flourishes we have at our disposal to create and talk about poems. And! The simultaneous long tradition and spirit of innovation in poetry—how we enter and interrogate an ongoing, “happening-since-ancient-times-but-made-new-all-the-time” conversation when we read and write poems.

I hope to share my passion and experience with my workshop; I hope for us to learn from each other, too.

To find out more about Michelle Peñaloza, check out her website at michellepenaloza.com.

Applications for scholarships to MCWC 2020 will open January 1, and general registration will open March 1. Visit our website after January 1 for the full faculty line-up and event schedule. Till then, you can take a look at MCWC 2019 at mcwc.org. And be sure to sign up for our monthly newsletter below for more faculty interviews and announcements.