Conference Assistant Frannie Deckas chats to Ayize Jama-Everett, instructor of the Speculative Fiction workshop at MCWC 2022, POV/Voice and Worldbuilding: The way through.

What are some of the people, places, things, and ideas that inspire you?

I've got my heroes like everyone, but the unifying factor in them all is an inability to live a life prescribed to them. I'm inspired by those who take ownership of their lives and don't let norms, trauma, or conventional thinking dictate their moves in the world. In terms of places, I've heard about an island full of dogs that sounds amazing. I like deserts and secluded large lakes, quiet places. But I also grew up in NYC, so I'm a sucker for good nightlife, at least I was before COVID. Now the thought of being around a mass of strangers is a bit daunting to me. Still, though, the magic of the dance floor is always on my mind.

What does your ideation process look like for a new book?

Percolation, percolation, percolation + mind-numbing tedium called typing X burst of inspirational jotting/reading said accumulations of letters on the page, bracketed by an inability to stop=A novel, short story, or graphic novel. That makes sense, right? I write. When I have enough down that I think it makes sense, I read it. Then I figure out what else to write. Rinse and repeat until someone else tells me it's done. I think there's a belief that I've helped to perpetuate, that writers are self-aware and know what we're doing most of the time. The older I get, the more seasoned in the game, I realize that the best writing comes from being open to being wrong about everything I'm doing but doing it anyway. For instance, I have a cult novel, my cult novel. My obsession with intentional communities has persisted since I was four-years-old. I have at least 200 pages of a good cult novel. But just last week, after realizing that someone I'm very close to has been in two cults in her life, I realized my angle on the novel was wrong. So those 200 pages will probably never come to light. Something will come out of them, but if I try and make those pages my cult novel, I'll be doing a disservice to what I know to be true. What's that? Ideation? Trying something and screwing up? Being open to failure? Bad writing? I call it my process :)

Sometimes, when writing, voice can feel like it wants to hang on into the next work. How do you make the shift in voice between one story to the next?

Usually, through POV (point of view), omniscient narrators are no longer in favor. Still, I'll say that most narratives I start have that god-like overview of the world, the character's psyche, and the future of the narrative (though that often time tends to be false). What I burrow into, what makes it fun for me, is to strip away all that insight by focusing on one character or a set of characters. It's like a flashlight that can only cast so much brilliance in front of them. Like us all, the characters fumble in the dark, pretending they're aware of the world around them in total. When in actuality, we're all just trying to give ourselves a little bit of security with the lie, "It's not that dark in here." Voice, for me, comes from the tone of that lie and the amount of luminance surrounding the character. I tend to write intimate stories, with characters doing their best to pay attention only to what's in front of them. It's the world that invades their space, not the other way around. So the character's voice is determined by how they deal with the unknown. The narrative's voice is determined by how much knowledge I choose to convey to the reader.

What's your best advice on writing flawed but redeemable characters?

The hero is the cult of the dead. Please don't have them seek out redemption. Hercules killed four mythical creatures, captured three more, and stole a goddess girdle to atone for killing his wife. Is that redemption? I guess for the times, it was. So make redemption culturally specific and intriguing if you're going to do that. I don't need redeemed characters. I need characters who make choices, hard choices and live with the consequences. I like Giles Corey from the Crucible asking for more weight. I like Marv from Sin City getting electrocuted only to ask, "Is that all you got?"

Flawed characters are characters. They're human. And while audiences like to read about how a character changes over time, I don't think every novel needs to mimic therapy; by this, I mean it doesn't have to be a standard arc of improvement for a character. We can revel in their flaws, or we can be disgusted by them, but they've got to have those dings in their armor so we can relate to them. This is why for the most part, I don't like Superman. It's not the ubiquity of his powers; it's the fact that he never has a moral failing. It's why I love Daredevil. A blind lawyer goes out at night dressed like a devil and fights the wealthiest and most wealthy people his lawyering can't touch. Show me someone stuck in a constant moral compromise, and you show me someone as flawed as we all are. That's the beginning of piquing my interest: Kerouac's Dean Moriarty the perfect example. A flawed character never to be redeemed but at the same time a literary zeitgeist.

What, if anything, do you translate from your own life into the lives of your characters?

Damn near everything! What else am I to draw from? Even if I do my research, it's how the study hits my ears, eyes, and heart. The fun part of writing, which some have taken too far, is to live a life worthy of drawing from. That's why we're about to have a flood of novels about being locked down, locked in, pandemic length relationships, and the tentative nature of the social contract. :) We've all been living through the same thing globally.

How do you build on POV to create your story world?

No world exists without characters to experience it. The POV allows the writer to zoom in or out of any particular aspect of the world that impresses the character. But just as all knowledge is subjective, so too is the focus. What may seem like a close read to a first-person narrator maybe be frivolous to a third person. I find it interesting that these POV's come in and out of style. I'm sure there's some macro psychological reason as to why, but damned if I can call it.

I had an opportunity to write up an interview in the second person. It was of Ahmed Best, the dancer, singer, musician, and all-around great guy who, among other roles, played Jar Jar Binks. That role haunted him and caused a lot of people to question his standing in the Black artistic community. I'll confess that I had some of those questions myself. Man, I felt like an asshole after hanging out with that man. He was so charming, so kind, so generous. He shared what it had been like to him to be ostracized by both the Black community (those that knew it was him playing the role and disagreed with its depiction) AND the Star Wars fans. He became suicidal briefly. Thankfully, he got the help he needed and is now thriving and being his usual excellent self.

Anyway, the interview was for a class Tom Lutz was teaching, then editor in chief of the L.A. review of books. I wanted people to feel Ahmed the way I thought him, to experience his highs and lows the way I did. So I pitched writing the interview in the second person. "You're Ahmed Best. You're fifteen and your mother has just recorded another album. You commit yourself to creating an album of your own". That sort of thing. Tom Lutz was not a fan, but he hit me with the "Prove me wrong" like all great teachers. So I wrote it up...and he loved it. That's the power of the proper POV. It adds the dimension of the Lacanian Real, the inarticulate, to a narrative. It's also a convention of the time, the metastructure through which the audience expects the narrative.

About Ayize

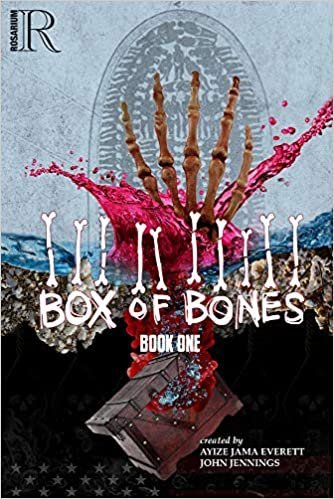

Ayize Jama-Everett was born in 1974 in Harlem New York. He has traveled extensively in Northern Africa, Northern California, and Oaxaca, Mexico. He holds three Master’s degrees (Divinity, Psychology, and creative writing), and has worked as a bookseller, professor, and therapist. He has a firm desire to create stories that people want to read. He believes the narratives of our times dictate future realities; he’s invested in working subversive notions like family of choice, striving when not chosen to survive, and irrational optimism into his creations. Three of his books have been published by Small Beer Press, The Liminal series, with another on the way. He’s published a graphic novel with noted artist John Jennings, entitled The Box of Bones, and has forthcoming a graphic novel adaptation of The Count of Monte Cristo coming from Abrams Press. Shorter works can be found in The Believer, LA Review of Books, and Racebaitr.